Editor’s Note: Our guest contributor is Sally MacDonald from Atlanta. She shared reflections on a biography of John Lewis last year. Today she writes about civil rights leader and theologian Howard Thurman and his views on faith and justice.

I write this post with the echo of MLK’s 2022 holiday celebration still reverberating. Just as we honor his legacy, we recognize those who came before him to guide and inspire.

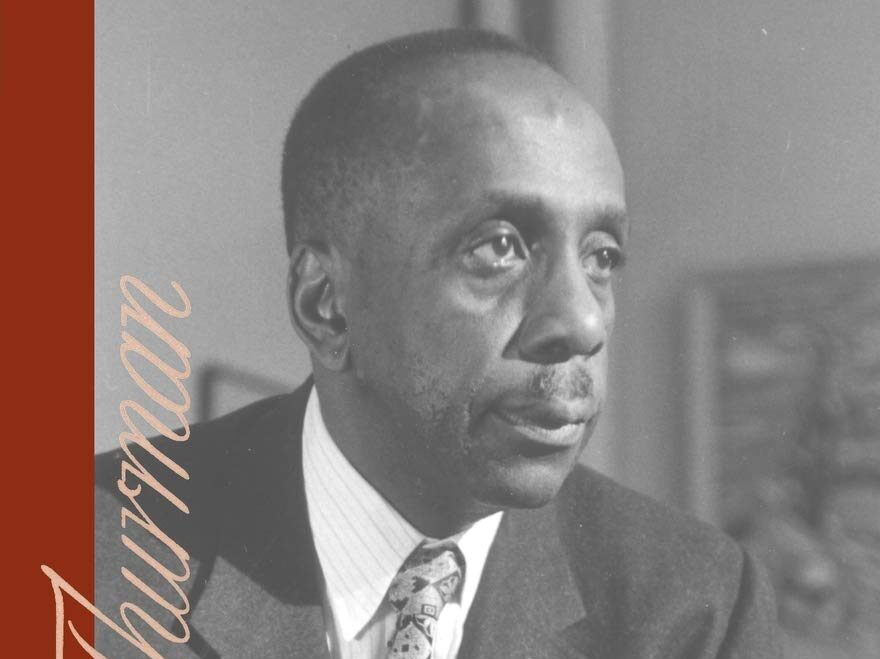

One who came before was Howard Thurman (1899-1981). He’s been considered a visionary, mystic, and prophet. His 1935 essay, “Good News for the Underprivileged” paved the way for his 1949 book, Jesus and the Disinherited.

Thurman left FL in 1919 for Morehouse College in Atlanta, where he discussed concerns with his contemporary, Martin Luther King, Sr., and faculty members Benjamin E. Mays and Franklin Frazier. This training prepared him for Rochester Theological Seminary in Rochester, NY and later Howard University, D.C. in 1935. Pioneers in radical nonviolence, Nelson Mandela and Ella Baker were influencing him then.

He came to possess a letter from Mahatma Gandhi to Muriel Lester that directed, “Speak the truth without fear”; this was a bedrock for him. Thurman did not share Gandhi’s Hindu faith, but they were united in their respect for truthfulness when confronting the “oppressor.”

In Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman lays out his faith relationship to Jesus Christ and fleshes out the actions required by that faith. Thurman explains a Jim Crow South where oppression was codified both de jure and de facto. He describes the fear that overtakes the oppressed blacks when power relies on actual and implied violence to control.

Thurman uses the metaphor of the disinherited with their backs against the wall. Survival dictates the coping mechanism of Deception. The author understands it, yet does not promote it. It’s a rational scheme when dishonesty undergirds an unjust society. As an example, black slave spirituals coded messages about escape and freedom that were too dangerous to speak outright.

Human beings accommodate to their environment. Thurman tackles hate as the most toxic of these reactions to an untenable reality. This chilling quote references his overhearing two black teenage girls on a train who, upon seeing 2 white girls skate toward the train said, “Wouldn’t it be funny if they fell and spattered their brains all over the pavement?” It made him shiver. He knew that their hatred probably was linked to some experience that had rusted their souls with bitterness.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper had the headline recently that “MLK knew the power of redemptive love.” Thurman ends his book with the same transformative antidote, love. One cannot practice radical nonviolence without loving the oppressor. It is no easier today than it was in 1949, or in any of the decades since. When we love our enemies, we honor both our humanities. We become “free at last, free at last,” the Gospel spiritual Thurman quotes in his book, and MLK uses to end his “I have a dream” speech in 1963.

Thurman’s faith translated this love into fellowship. When this book was published, Thurman was leading the nation’s first intentionally integrated congregation, the Church for the Fellowship of all People, in San Francisco. He bemoaned the notion that congregations separate by “class, race, power, status and wealth.” He considered these the “chief instruments for guaranteeing barriers.”

It’s evident that Howard Thurman put his faith into action. It spawned ramifications that outlived him to present day. Leo Tolstoy wrote, circa 1910, “Don’t think that you can find peace for your soul without faith.”

Thank you sharing these insights into the mind and spirit of one of the too often neglected giants and wise souls of the 20th Century, indeed in my mind of all time.

Thanks Robin, indeed Howard Thurman is an unexplored treasure for too many of us, peace, Tom