As I paused and reflected yesterday on the life of Martin Luther King, Jr. and his legacy, it was hard to avoid wanting a clear report card on the progress made on his mission. As I pondered the question, “How are we doing in becoming a more equal and just nation?”, my first thoughts were all negative.

This internal debate had started the previous weekend when I saw the new West Side Story in a theatre with mandated Covid protections. This story vividly replays the tragic and violent turf war between poor, left-behind, young white men and recently-arrived young immigrants from Puerto Rico. West Side Story was first seen as a Broadway play in 1957 and then in an adapted movie version in 1961.

Over sixty years ago, the creative team of Jerome Robbins, Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim had the courage to introduce in the story a number of themes that were seen as quite radical at the time. The play was clear about the racism that drove the fierce rivalry. It went head-on at the taboo subject of interracial relationships and marriage. And it depicted how local governments used slum clearance to displace poor people to create housing and cultural venues for middle- and upper-income people.

My first reaction to seeing this movie was a deep sadness that so many of the issues are still front and center six decades later. It is not hard to substitute the current fight by white supremacists to keep control of America for the battle of the movie’s white gang to keep its turf on the west side of Manhattan.

Both then and now, the idea of preserving white control is an apartheid fantasy. This desire seems driven by fear and a desperate feeling of being left behind, left out. A recent conversation with an older friend about why we should focus on “all lives matter,” not Black Lives Matter, reminded me of this fear. While my friend was willing to acknowledge that poor white people did not arrive as slaves and do not face automatic discrimination because of skin color and structural racism, he was unwilling to see Black Lives Matter as a statement of this racial difference and of the need to address racism against Blacks.

Ironically these reflections led me to begin to shift to less hopelessness about the lack of progress some fifty years since Dr. King’s murder. But less hopelessness is a long way from optimism. The murders of Black people and people of color continue. But we do have, for those who want it, much greater access to a more accurate history of the racist practices adopted by the dominant white population that have caused the racial disparities between whites and Black and brown people in educational outcomes, in family wealth and in any other category of wellbeing you want to pick

What gave me some hope was not progress on data points that illustrate that history. No, I took solace in the possibility of compassion and in the fact that the fear and hate are no longer disguised. The ugliness of racism in America is as obvious today as it was when the KKK was lynching Black people. What’s different and gives hope is that there are more eyes open to racism and still more open to considering new ways to make reparations for and end the ugliness of our past. This is slow progress for sure, yet it appears to be progress.

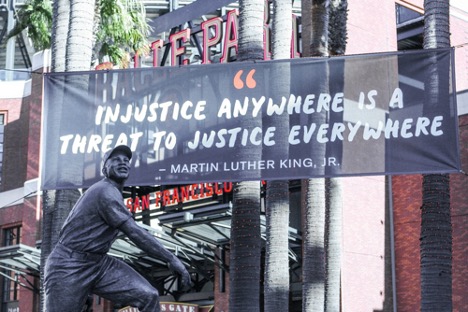

Martin Luther King, Jr. modeled what is meant by working for justice and keeping love in his heart. He hated the deeds, not the perpetrators of the deeds. He and thousands of Black and Brown leaders have taught us all what compassion means. The fact that our nation has survived so many years with this deep underbelly of racial hate and conflict is indeed a miracle. And much of the miracle comes from the generous tolerance of people of color.

As we move through this very divisive and still ugly time, I take solace in the belief that what we are experiencing is necessary to get to a place where the justice and love Dr. King preached and lived are our norm and way of life.

As you reflect on Dr. King and his legacy, what brings you hope or despair? What actions are calling you to advance justice and compassion? Hope and action are connected.

For those inclined to pray, we might consider this prayer from Dr. King: “We are not satisfied with the world as we have found it. It is too little the kingdom of God as yet. Grant us the privilege of a part in its regeneration.”

https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/prayers

As usual, I think you bring deeper clarity, hope and a gentle push to change what we can on an ongoing situation we are part of no matter who we are. Many thanks!

Thanks Mary for your observations and reminder of how we might apply the serenity prayer to our actions for racial justice. I listened to parts of two of Martin Luther King’s sermons yesterday. One was at Garce Cathedral in San Francisco and another his last I think at National Cathedral. He referecned the book of Apocalypse and John in both and spoke of our need for universal sisterhood and brotherhood to make real the kingdom of God. Peace, Tom

When King used the metaphor of being a drum major for peace, he alerted us that peace-making can be disruptive and unsettling. He gave his life; John Lewis got his head bashed. Indeed, our nation has survived a Civil War that took thousands of lives. The jury is out as to how we retain our democracy in the midst of rifts and subsequent violence. What propels me is the promise that being on the “right side of history’ is its own reward. Teresa of Calcutta reminded us to be obedient, not necessarily successful. I remain vigilant in my own sphere, following Gandhi’s advice, “Be the change you want to see in the world.”

Thanks Sally, yes it is amazing and wonderful that so many courageous people have gone before us and left bread crumbs and big clues on how to move thru discord and disharmony. Thanks for the reminders. Tom